- + (911) 1987 123456

- chair@kensingtoncourtresidents.org

- Kensington Court London

PIONEERING IN KENSINGTON COURT

ELECTRIC LIGHT

Whatever the architectural merits of Stevenson’s houses, two technical innovations give them an historic place in the story of urban development. They were the first domestic buildings in Britain to be supplied with electricity and hydraulic power on a permanent basis.

Electricity was distributed from the a building in the north-west corner of Kensington Court, just by the passage way to Kensington High Street. There’s a blue plaque on the wall of No 46 to the pioneering engineer who supplied it – Colonel Crompton. The Colonel had his home and workshops here. It is reputedly the first steel framed house in Britain. Just behind it he had already built a generating station which provided electric power to the new houses in Kensington Court – a pioneering achievement that put this middle class community at the cutting edge of urban technology.

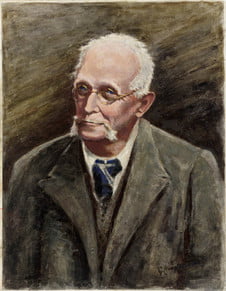

Colonel Rookes Evelyn Bell Crompton, to give him his full name, was a remarkable man, though little known these days. He was one of Britain’s most distinguished electrical engineers, an inventor and a pioneer of electric lighting and the public supply of electricity. Among his early achievements were installing electric lights in Windsor Castle, King’s Cross Station and the Vienna State Opera House. But his connection with Kensington Court is equally historic.

In the building now occupied by Warner’s Music in Kensington Court Passageway, Crompton built one of the first ever power stations to supply electricity to the public - in this case, to the newly built houses in Kensington Court. Seven steam engines coupled to Crompton dynamos supplied power from an underground turbine room. So successful was the system that his company went on to install similar ones all over the world. However it wasn’t without its dangers. Crompton lived next door to his power station at no 46, the big building on the corner of Kensington Court. In 1895 a fire broke out in the power station and he took an active part fighting the blaze and preventing it reaching the fuel oil stored there. At one stage he had to man-handle fire hoses through his front door, across the floors of his house and out the back windows, which faced the rear of the power station. He received several electric shocks and burns from a flooded battery bank. Not bad for a 50 year old! He went on to invent the first electric toaster and the world’s first widely-sold electric oven. He died in 1940, aged 95.

HYDRAULIC POWER

In the South east corner of Kensington Court is a plain brick 4 storied building, quite unlike the more ornate flats that surround it. Even curiouser, on it is a sign saying 'The Old Pump House'. It is witness to the other pioneering innovation that marked the creation of Kensington Court.

In the 1880s there was a new source of power throughout Central London – water power, provided by the London Hydraulic Power Company. It was supplied at a pressure of 700lb per sq.in. through a network of underground pipes (180 miles of them at their peak) to power machinery and lifts in factories, hotels and offices. In 1884, Kensington Court’s developer, Jonathan Carr, decided to give the houses he was building an added attraction – hydraulically-powered service lifts in place of back stairs. So he persuaded the London Hydraulic Power Co to build a pumping station specifically for Kensington Court, independent of its main supply. This is the Old Pump House and explains why the building looks so different. Originally it did not have any windows, as it housed pumping engines, boilers and a giant accumulator in its tower. From here, water at 400-450 lbs per sq. in. was supplied to the houses through a system of pipes along the large subways that Carr had also built under the roads of Kensington Court. It was a striking innovation and the first time in Britain that this kind of hydraulic system was used to power domestic houses. But it appears not to have been economic, because in 1892 the pumping plant was shut down and Kensington Court connected to the mains hydraulic supply. In 1928 some lifts were still working hydraulically – but no longer. The London Hydraulic Power Company finally closed in 1977. It sold its underground pipes to the UK’s first mobile phone operator, Mercury Communications, which in due course became Virgin Mobile. So now instead of bringing us hydraulic power, those pipes deliver cable television.